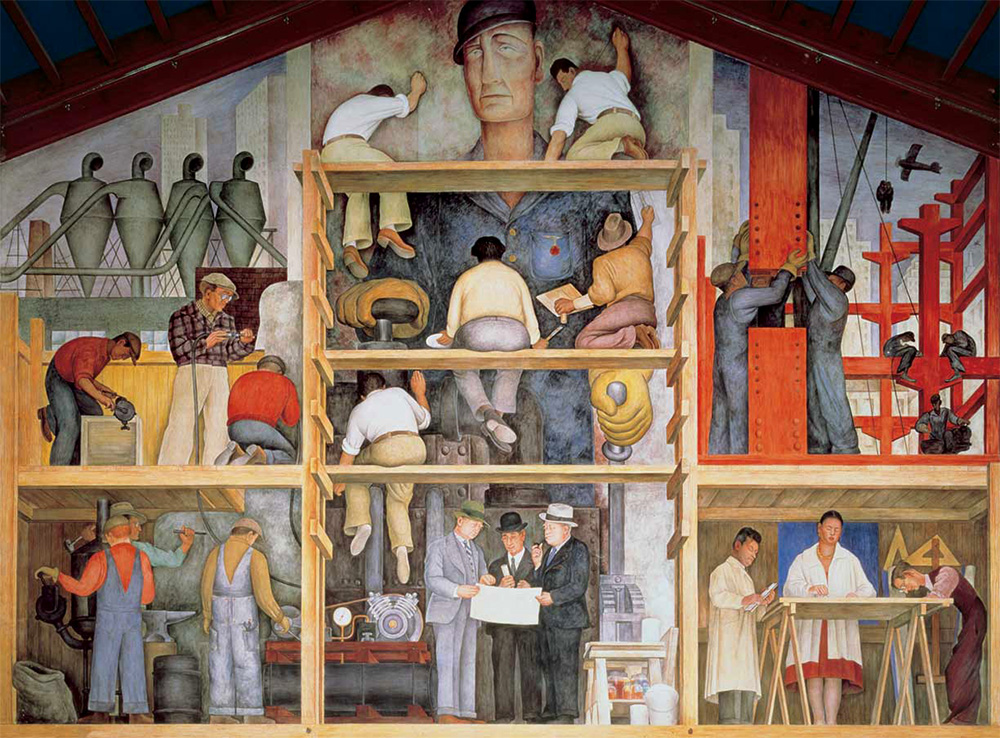

This is Diego Rivera’s mural The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City. Completed in a month in May 1931, it is in the San Francisco Art Institute. You can just walk in off the (very steep – this is San Francisco) street to see it (800 Chestnut Street, 9am to 7pm). That makes it probably the most accessible of Rivera’s murals for this project’s readership – most of whom, I guess, are more likely to make it to San Francisco than to Mexico City or Detroit.

Art history hasn’t been entirely fair to Rivera. When the story of modern art was seen as the shining path to abstract expressionism, Rivera together with Jose Clemente Orozco and David A Siqueiros, the other ‘big three’ great Mexican muralists, were often conveniently left out as being ‘social realists’ and too concerned with politics. More recently he is often assigned (probably unjustly) an inglorious bit-part as Frida Kahlo’s feckless other half.

Rivera is also not well served by art museums, though you can find plenty of his works there. Before his murals he spent more than a decade in Europe (1907 to 1921) and became an accomplished modernist (particularly cubist), but also missed the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) he later did so much to celebrate. During his international glory days in the 1930s he did some great portraits (including one of Edsel Ford, who also commissioned magnificent Rivera murals in Detroit). And he painted numerous pictures of Mexican popular life, most famously flower sellers (personally I find these a bit on the sentimental side). The problem is that easel paintings, however good, don’t do justice to Rivera’s extraordinary talents. To really experience them you have to see the murals – and walls, by and large, don’t travel.

Making of a Fresco isn’t by any means the biggest of them – Rivera complained that the wall offered to him was ‘a small one of only 36 square metres’ (in fact the total area of the finished mural is 43.2 square metres) ‘not at all suitable to my purpose, which was to present a dynamic concerto of construction – technicians, planners and artists working together to create a modern edifice’.

But it is easily big enough to see what makes Rivera so good. First there is the way he fills the space – not a square centimetre wasted – with absorbing and utterly comprehensible interlocking narratives. Then there is the way he deals so easily with modern life – socially but always preserving individuality. The big bum on the trestle in the middle obviously belongs to Rivera himself, but the other painters with their backs to us are his assistants – Matthew Barnes on his right; John Hastings next floor of scaffolding down on his left; and in the lower panel on the right, hard at work at the trestle table, the trio of designer Michael Goodman, Art Institute lecturer Geraldine Colby Fricke and engineer Alfred Barrows. Rivera’s hugely distinctive work applies all sorts of techniques and ideas from the Renaissance, from his use of fresco (paint applied to wet plaster) to the prominently featured ‘donors’ reminiscent of so many fifteenth and sixteenth century European religious paintings – in this case the hatted and suited trio examining plans, Timothy Pflueger, the architect who invited Rivera to San Francisco to paint a mural in the stock exchange, William Gerstle the chairman of the San Francisco Art Commission who commissioned the Art Institute mural, and Arthur Brown architect of the Institute.

And finally, there is Rivera’s ability to master a commission, while still maintaining his own, social and political concerns. This is a mural for an art school, so it is a fresco about making a fresco. It is a mural in a dynamic North American city of the 1930s, so it is about design and construction in such a city. But alongside that it celebrates the dignity of workers by hand and by brain.

Generally, Rivera got away with it – with satisfied patrons including Edsel Ford and the Mexican government. Once, famously, he didn’t, when Nelson Rockefeller discovered that Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads for the new Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan included a portrait of Lenin. Rockefeller promptly paid Rivera off and – to the eternal loss of New Yorkers – a year later destroyed the not-quite completed fresco. When Rivera re-created the work the following year at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, Lenin was firmly there, this time alongside Trotsky and his call to create a Fourth International.

If Making of a Fresco whets your appetite, and I am sure it will, then half an hour’s drive away and a bit off the tourist track at City College of San Francisco (50 Phelan Avenue, check opening times but probably 10am to 4pm Mon to Sat in term time), is another, bigger and altogether wilder Rivera mural. Pan American Unity: The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and South of the Continent was painted for the 1939-1940 International Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco. Across ten panels and covering a total of 175 square metres every aspect of the title, and more, is explored: from the recently constructed Bay Bridge to pre-Conquest Aztec craftsmen and women; Simon Bolivar alongside Abraham Lincoln; Charlie Chaplin and Frank Lloyd Wright; the murderous trio of Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini; and a statuesque Frida Kahlo ( who remarried Rivera in 1940 in San Francisco) rather curiously standing right in front of Rivera himself, who has his back to her and is holding hands with the Hollywood star Paulette Godard.

And if Pan American Unity whets your appetite even more, there are of course flights to Detroit, and a few days holiday in Mexico City to be planned.

Peter Goodwin